On the 2d of March, 1827, a land grant was made to the state of Illinois, for the purpose of aiding in the building of the Illinois & Michigan canal, whose western terminus was fixed at this point in 1836. The grant comprised each alternate section for five miles on both sides of the line of the canal; the selection to be made by the commissioners of the land office. They chose the odd sections, the even sections being retained by the Government. In 1829 the state created a board of Canal Commissioners and the line was surveyed in the fall of the following year, 1830.

The natural wealth of this part of Illinois how began to attract the attention of pioneers, and it is about this period that the first settlements on or near the present site of the city are recorded. Simon Crozier, an Indian trader, is supposed to have had the honor of heralding the coming man. He built his house on the south side of the river near Shippingsport. His descendants are now residing near Utica.

In 1830 Samuel Lapsley came here from St. Louis and built a log house which stood until a few years ago between Fourth and Fifth streets, north of the Christian Brothers' Academy. He cultivated a tract of land which extended as far north as Fifth street and as far east as Joliet street, bordered by the bluff south and by a ravine on the west. On this he raised corn and wheat. When the State took possession of the canal land he lost his improvements. His death occurred in 1839.

In the spring of 1830 commissioners sent by some young men in the east to select the site for a colony which they wished to establish in Illinois, fixed upon this point. Their choice was determined by the richness of the land, the reported existence of immense coal beds, and the superior land and water communications promised by the early completion of the canal and railroads. About this time Burton Ayres arrived from Ohio and built a cabin one-half mile northwest of the spot now occupied by Matthiessen & Hegeler's rolling-mill, where he also erected a blacksmith shop and made plows for the Massachusetts colonists, who followed him in the spring of 1831, Aaron Gunn, sr., being among the number. The season proving a rainy one, the young colonists became discouraged and removed to Princeton and La Moille. The war with the Indian chief Black Hawk breaking out in 1832, the white settlers were driven from La Moille, Aaron Gunn going to Hennepin. The latter returned to La Salle in 1835, Government land being offered for sale in that year, and purchased 400 acres north of the canal section.

In 1835 D. Lathrop was sent by the Rockwell Land Co. of Norwich, Conn., of which he was a member, to purchase land for the purpose of speculation. He selected the half section now known as Rockwell, supposing that the city which should arise at the crossing of the river by the projected Illinois Central railroad and at the terminus of the canal would probably be located here, and made his choice accordingly. In the winter of 1837-38 he returned to Connecticut and started out with a colony of about one hundred and thirty persons, many of whom dropped off at points along the river. Among those who reached this point were Mrs. George Neu of Homer, D. Carr of Bachelor's Ridge and Miss Serls, now Mrs. Elisha Merritt. A number of this party died with the cholera, which broke out shortly after their settlement.

In the spring of 1837 the city was laid out on section 15, canal land, leaving those who had previously purchased from the government land on which they anticipated the city would stand, entirely beyond its limits. The first sale of city lots was made in 1838. The old Central railroad, which the State undertook to build, was graded through La Salle in 1839-40, the subsequent bankruptcy of the State preventing its final completion. The construction of the canal was begun in 1836 but work was discontinued in 1841. In 1845 the work was again resumed and completed in 1848, the first boat which passed through the locks at this place being the Gen. Thornton built by Isaac Hardy. At this time the total population of La Salle was only 200. The visitation of the Asiatic Cholera in 1849 and '52 proved a most terrible scourge, retarding the growth not only of La Salle but of all western towns, many of the settlers dying while others fled the country.

It was a number of years before business recovered from the shock it received on the occasion of the State going into bankruptcy in 1841. But the development of the resources of Illinois was not to be stopped by a single financial crisis. Emigration still continued though for a while it was very limited; business in time however received a new impulse and the construction of railroads was again undertaken. The Chicago & Rock Island, now the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific railroad was built through here in 1853, and the next year the Illinois Central railroad bridge across the river was finished, the two portions of the road previously completed being connected.

The first church within the limits of La Salle was a log structure built by Fathers Rowe and Parodi, in the year 1838, on the present site of the Brothers' Academy. In 1848 a building to be used as a school house and a Baptist church was constructed on the corner of Fifth and Marquette streets. This was the first school house. It was subsequently removed and is now used as a dwelling. The present Catholic church was begun in 1846 and finished in 1852. It has since been enlarged and improved, and now forms one of the finest church edifices west of Chicago. The old school building standing in the northern part of the town was built about the year 1855 by a stock company for the purpose of a high school. Little success attended the efforts of those engaged in the enterprise and the project was shortly afterwards abandoned.

Man proposes, but God disposes. The trouble with man is that he can never make due allowance for what ingenious contrivance his fellowman will be at next. It was so with the founders of La Salle. It was laid out in the days when railways were but little known in the West and the opening up of water routes was considered the only available means by which to encourage and secure the settlement and development of this region. The Illinois and Michigan Canal was to be the making of the city and when it was dug Chicago was the only city in the State which it was believed could rival the maritime metropolis that was destined to nourish at the junction of this water course and the Illinois River. The termination of the canal, it may be remarked, was not fixed at this particular point because it was not possible for boats to ascend further up the river, but because, while the bill for its establishment was pending in the State Legislature, there chanced to be, in order to secure its passage, a necessity for another vote in its favor, and this vote was only to be obtained on condition that the proposed route of the canal be changed so as to connect with the river here instead of at the actual head of navigation, old Utica, about five miles farther east. However, founded and nourished through the instrumentality of the river and canal, La Salle grew and prospered, but did not exactly develop into a city second only to Chicago, for the reason that before the anticipated accumulation of wealth, business and population were attained, a wide-reaching system of railways had spread out over the country, and water transportation lost its prestige as the grand requisite for commercial wealth and extensive business transactions. La Salle was not to become a commercial city. It was to be a producer and not a trader, and the railways so effectually superseding water-ways as avenues of intercommunication, while they ruined prior hopes and expectations, opened the way for the development of resources at first little known and the real value of which had not been before anticipated. The coal found here, with the facilities by rail and water for transportation in all directions, have been the agencies which made possible the building up of the extensive factories now in existence at this point, and continually enlarging and increasing in numbers.

The location of La Salle is one of the most picturesque on the Illinois River, and is in sight of the historic "Starved Rock," on whose summit was closed, about 1770, the final act in the great tragedy commenced a hundred years before, and only a few miles distant to the westward, which resulted in the total destruction of the once powerful Illinois Indians by their inveterate enemies, the Iroquois. One of the most beautiful views perhaps in the entire State can be obtained from a summit near the eastern limit of the city, the eye readily taking in an immense stretch of wooded bluff, cultivated plain and winding river, variegated with villages, railway lines and bridges. One of the last mentioned, the Illinois Central, lacks only a little of being a mile in length, an iron truss supported on eighteen heavy piers, with a roadway almost a hundred feet above the surface of the river.

The population is about 10,000. More than a thousand coal miners find regular employment, and half as many men are engaged in the manufacture of zinc, while the glass works and other manufacturing establishments give employment to many more.

The mineral products of the vicinity, though not embracing precious metals to any alarming extent, are numerous, consisting in coal in inexhaustible quantities, the field extending over about fifty square miles and being underlaid with three veins varying in thickness from three feet six inches to four feet eight inches; fire clay, much of which is manufactured into brick, tile, sewer pipe, etc., here, and large amounts annually shipped to other points for use in furnaces and for other purposes; cement rock, from which hydraulic cement is made; glass sand, said to be far superior to that found in the Pittsburg region; very large yellow ochre deposits, which have not thus far been utilized, with immense ledges of marble, which has not yet worked its way into popular favor. Large beds of gravel also exist here and considerable quantities have been used for macadamizing roads in the surrounding country and the streets of the city.

The coal, which has been the real foundation of the wealth of the locality, was discovered by the early explorers of the country. The first mining was done by "drifting," as it is called, or taking out the coal from the out-crops on the hill-sides. The first boring for coal to determine its depth below the surface, quality, thickness of vein, etc., was made by Dixwell Lathrop, recently deceased, near the canal basin in the winter of 1853-4. The following year what is known as the Kentucky shaft was sunk and the next year the La Salle shaft, both now the property of the La Salle Coal Mining Company, which also owns the Rockwell or Carbon shaft, sunk about 1865. In the immediate vicinity there are eleven shafts open, nine of which are operated, the coal firms numbering seven. The total capacity of these shafts combined aggregate somewhat over 1,000,000 tons annually. The La Salle shaft, which is a leading and representative one, is 400 feet deep, extending to the third vein. The first vein is in no case operated; the second is largely worked in this and many of the other shafts, but the third furnishes by far the best coal. Although coal has been mined here continually for twenty-five years the supply is not perceptibly diminished, the fact being that the mine is not yet adequately developed for its most successful operation. The entries radiate principally eastward from the bottom of the shaft, many being over a mile in length. From the distant parts the coal is hauled in cars holding 3,000 pounds, by mules to the cage or carriage on which they are elevated to the surface by steam power. The shaft is about 10x20 feet square, lined with timbers with a partition in the middle, each side equipped with a cage, one of which is lowered while the other is being raised, both being operated simultaneously by means of wire cables wound on a drum.

Glass was first manufactured here about twenty years ago, but the business was not very successful financially until recently, or since the De Steiger Glass Company was organized in 1878. This company put up new factories, purchased those formerly built, and entered largely into the manufacture of both bottles and window glass, with a determination to succeed if success could be attained by pushing business. They have always found sale for all the glass they could make, and often experienced difficulty in filling their orders. In methods and apparatus they are now in advance of anything heretofore known in the United States. Noticing that large importations of bottles were being made from Europe into this country, notwithstanding the import duty of 30 per cent ad valorem, they resolved to make, in all necessary respects such changes in their factory as would enable them to put on the market as good a bottle as could be imported.

The principal difficulties to be overcome were the obstacles placed in the way by the Bottle Blowers' League, an organization which has persistently stood in its own light for years, and caused a great deal of trouble and immense loss to the proprietors of glass factories by the strict observance of arbitrary rules adopted for the supposed protection of the membership. During the summer of '80 the old employees of the company were discharged, and a number of German bottle blowers imported, despite the combined efforts of the German Government and the League to prevent it. These men work differently from the Americans, particularly in turning the bottle in the mold during the blowing process, a straw or shaving being placed in it previous to the insertion of the glass. This gives the bottle a smooth or polished appearance, without seams, and makes it compare with the ordinary American made bottle about as a plate-glass window does with a skylight. In order to further facilitate and economize labor the company built, during the summer and fall, a Sieman's continuous tank, largely used by European glass manufacturers, but, with the exception of one at Poughkeepsie, N. Y., lately destroyed by fire, never before constructed in this country. It is a huge reservoir, eighteen feet wide, forty feet long and four feet deep, made of blocks of fireclay. It is arched over with imported fire brick and is round at one end. It is supported on heavy masses of brick work. Adjacent to it are furnaces for the production of gas with which to produce the requisite heat for its operation. This passes from the generator down through pipes below the tank and burns while passing up through checkered brick work where it comes in contact with the air, and subsequently through flues at each side of the tank under the arch, and over the molten glass. No heat is applied to the bottom. The tank holds 200 tons of glass, is fed at one end and the glass is taken from the other, or the circular end, for blowing. The advantages claimed for this over the old methods are that blowing will not have to be discontinued from twelve to fourteen hours every day to allow the pots to be recharged. Work can go on continuously night and day. The quality of the glass will be perfectly uniform as also the color; no heat will be lost as in the case of pots, the gas being admitted first from one side of the tank and then from the other, alternating about every fifteen or twenty minutes; there is no loss from the breaking of pots, while the expense of fuel is kept at a minimum. Probably the principal reason why these tanks have not heretofore been used in this country is that the glass-blowers' organizations have forbidden their members to do night work, with the view of preventing over-production, and as the heat must be maintained at all times for the preservation of the tank the gain in other respects would be more than counterbalanced by the enforced loss of time. Aiming to protect themselves, the glass-blowers have actually stood in the way of progress in their own branch of art. The members of the Bottle Blowers' League and former employees have expressed great indignation at this action of the De Steiger Glass Company, but the step was taken in self-defense and is a wide departure from the long established practices of American glass makers, nevertheless a departure which the public, as far as it is interested, heartily indorses, and other glass manufacturers will beyond any doubt soon follow in the wake of the De Steiger Company.

The zinc industry, which is now by far the largest in the United States, was begun in 1858 by Messrs. Mattheissen & Hegeler. For eight years they confined themselves to the manufacture of spelter only, but in 1866 erected their rolling mill. They heretofore virtually controlled the zinc trade of the country. Having no competition worthy the name in the manufacture of sheet zinc, they, of course, controlled the market, and at the same time managed, by being large purchasers as well as producers of spelter, to govern the price of that article also. A wealthy company, which has been for years operating zinc furnaces in Peru, has in self-defense built a rolling mill of its own of a capacity little inferior, if not equal, to that of Mattheissen & Hegeler so that it shall no longer be at the mercy of its competitors.

The ore, which is either the sulphate, silicate or carbonate of zinc, is obtained principally from Wisconsin and Missouri, and costs a little less than $20 per ton besides freight. It is first pulverized in a crusher and then thoroughly washed, and, if the sulphate, roasted to drive off the sulphur. After this it is mixed with slack coal and put into retorts placed in an immense furnace heated by the combustion of gas from a Sieman's gas generator. The zinc comes out as an impalpable powder und is melted and cast into blocks, in which form it is known as spelter. The product, of the factory is not far from 10,000 tons annually. The coal consumption reaches 300 tons daily.

In order to utilize the sulphur from the ore which has heretofore been wasted Mattheissen & Hegeler have erected, and recently put into operation, a factory for the manufacture of sulphuric acid. An immense building, 60x450 feet in size, built of wood, thirty feet high, and supported on a series of timbers about fifteen feet high, contains the leaden chambers which entirely fill it, the weight of the lead used including, besides the chambers, pipes, tubing, etc., is 2,000,000 pounds. Adjacent to this. building stands the highest chimney in the State, it being in perpendicular height, above the foundations, 256 feet six inches. It is built of brick and stone, the inside diameter at the base being twenty feet, but only a few feet at the top. It is lined throughout with plaster of paris. The cost of erecting this factory will be very close to $200,000. The acid for the new glucose factory in Chicago will be made here.

The Mattlieissen & Hegeler zinc rolling mills occupy several buildings or rather one large building in several parts. The spelter is melted and cast in shallow pans perhaps 10x25 inches in size, and then passed to the rollers, which are huge cylinders of iron over two feet in diameter. There are five sets of these operated by two engines, the capacity of which combined is about 450 horse power. The zinc is passed through two sets of rollers and then cut and weighed, after which it is again rolled out still thinner, and when it has passed the last set of rollers is finally cut to the proper size for market and boxed ready for shipping.

The most prominent artificial characteristic of La Salle is Mattlieissen & Hegeler's big chimney. The last brick of the half million and more used in the construction of it was laid and the railing, promenade and iron work attached to the upper extremity during the early part of November. The exact diameter of the chimney inside is 19 feet 8 inches at the bottom and about 7 feet at the top; the thickness of the wall, starting from the foundation, is 2 feet 8 inches and at the top is 17 inches. The foundation walls extend 11 feet below the surface and in the whole structure there are above 550 cubic yards of solid masonry. Before the staging, which was all inside, was taken down, a pulley was attached to the railing surrounding the top and over it depends a rope, by means of which to draw up a man on an attached carriage, should it be necessary at any time to ascend the chimney. On the inside from the top to the bottom the masonry is heavily coated with pure plaster of Paris for the purpose of keeping the sulphuric acid from attacking the walls and eventually causing their ruin. The idea of dissolving up the huge chimney may seem as preposterous as the story of Hannibal dissolving the rocks that impeded the march of his troops over the Alps: but facts are facts, nevertheless, and the disintegration of the chimney, though not very rapid, would certainly follow the neglect to afford the masonry complete protection from contact with the powerful solvent. The acid fumes, of which there are more or less in the chimney at all times, would permeate the masonry and come in contact with the iron and doubtless other substances contained in the brick and with them form sulphates or other compounds of sulphur. It would also attack the lime in the mortar and stone and form sulphate of lime; and these chemical reactions constantly going on would have the effect in a good deal less than a hundred years to very materially endanger the stability of the structure. Plaster of Paris is sulphate of lime, or lime that has taken up all the sulphuric acid it can contain and is in consequence no longer susceptible to the action of the acid, and being thickly spread over the entire inside, it thus forms a complete barrier against acid depredations upon the brick and stone work.

The chimney built in connection with the glucose works in Chicago and which is now finished, is two feet lower than Matthiessen & Hegeler's and is described as the most noticeable erection of the kind in the city. Such being the case, La Salle can claim, without much chance for refutation, to have the highest chimney in the West.

Extracted 24 Aug 2018 by Norma Hass from City of La Salle, Historical and Descriptive, with A Business Review, published in 1882, pages 1-6.

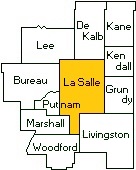

| Lee | DeKalb | Kane |

| Bureau |

|

Kendall |

| Putnam | Grundy | |

| Marshall | Woodford | Livingston |